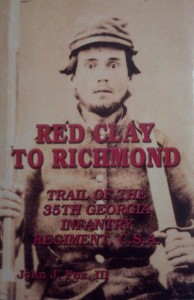

Ever since Red Clay to Richmond was released ten years ago, I have been asked many times about the 35th Georgia soldier on the cover. Well, that serious face with haunting eyes belonged to Private John Rigby from Company D, 35th Georgia. Before he enlisted in 1861, he was a sharecropper in Hogansville, Georgia. The bowie knife in the left hand and the bayonet-tipped rifle in the right seemed to foreshadow the tough battlefields he would soon cross as the image was probably taken in Richmond in early spring 1862 before he and his fellow Georgians had officially seen “the elephant” in a full-scale fight.

Rigby would be wounded on June 26, 1862 at the Battle of Mechanicsville at the beginning of the Seven Days’ Battles. Hit in the right thigh and left chest, he suffered a collapsed lung. Once his condition stabilized doctors sent him to convalesce at home in Troup County. While there his wife, Nancy, nursed him back to health and her heart must have broken again when he left in December to return to the fighting in Virginia. When they parted she would never see her husband again.

John somehow survived unscathed the heavy fighting of 1863 at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. He no doubt longed for a furlough back to Georgia, but by the winter of 1863-1864 the manpower shortage in the Army of Northern Virginia had reached epic numbers especially with James Longstreet’s corps detached to reinforce Braxton Bragg’s army in Georgia and Tennessee.

March 1864 found Edward Thomas’ Georgia Brigade [14th, 45th, 49th and 35th Georgia regiments] back in winter camp near Orange Court House with the rest of Robert E. Lee’s army. The Georgians had spent the previous three months in the Shenandoah Valley marching and countermarching in bitter cold trying to drive various Federal units away.

Then on May 2, “as if to foreshadow the coming violence of battle a horrendous thunderstorm passed over the Orange Court House area” flattening tents and scattering equipment. Two days later, numerous 35th Georgians attended a prayer meeting, but a courier soon arrived “with orders for the men to strike tents and to cook two days’ rations.” The Georgians departed camp that night around 10 pm. The column passed through Orange CH and then “turned east onto the Orange Plank Road toward Fredericksburg.” The Overland Campaign had begun.

What these Confederates didn’t know was that the Army of the Potomac was on the move from their winter camps around Culpeper. It would be a race to see if the Rebels could move far enough east to block the long blue columns moving across the Rapidan River toward the important crossroads where Wilderness Tavern stood.

Both armies banged into each other on May 5. As the sun began to set, Thomas’ men moved into the murky woods north of the Orange Plank Road and about a half-mile north of the Widow Tapp Farm. The Georgians soon found themselves fighting from three sides due to an attack by four brigades led by James Wadsworth out of the Union Fifth Corps. When all hope seemed lost, a rebel yell suddenly pierced the woods and “a thin line of 5th Alabama Battalion men, scrounged from a prisoner detail, swept onto the scene. They miraculously pushed back Wadworth’s first line. By the time the Union officers restored order to their ranks, it was dark” and another attack could not be mounted in the thick woods of the Wilderness.

Later that night, Thomas’ Georgians quietly pulled out of the area and moved to a position across the Orange Plank Road and just west of the Brock Road intersection. The fighting resumed at daylight on May 6. A strong Union infantry attack led by Winfield Hancock’s Second Corps pushed back the Confederate brigade on the Georgians right flank. Smoke from gunpowder and burning brush floated just above the ground. Then bullets zipped by from three sides again and Southern casualties mounted. Thomas’ panicked men began a chaotic withdrawal by their left flank.

Something struck John Rigby and he fell down as his colleagues swarmed toward the rear. The approaching line of blue-clad infantry soon gathered up Rigby and nearly fifty more 35th Georgians, most of them wounded. These unfortunate men soon found themselves at the notorious Union prison camp at Elmira, New York. Called “Hellmira” by most of the inhabitants, it became “infamous for having the highest prisoner mortality rate of any Northern prison camp.” At least ten of the captured 35th Georgians from the Wilderness fight would not walk out of Elmira alive.

Red Clay to Richmond:Trail of the 35th Georgia Infantry Regiment by John J. Fox III copyright 2004 Angle Valley Press

This sad list included John Rigby. He died of acute bronchitis on May 4, 1865 nearly a month after the surrender at Appomattox. He is buried at Elmira’s Woodlawn National Cemetery in grave #2756.

Nancy Rigby never learned the fate of her husband – whether he was killed on the battlefield or captured. Forever holding out hope that he would come home she “refused to apply for a government veteran’s pension until 1893.” When she died in 1897 her family buried her at Liberty Cemetery in Bremen, Georgia. Next to her grave stood an empty spot for John.

All of the above information came out of Red Clay to Richmond to Richmond: Trail of the 35th Georgia published by Angle Valley Press [2004]. I would like to again thank the Pollard and Mullinax families for giving me so much information on their great-great grandfather, John Rigby, and for allowing me to use his image on the cover of the book.

Speak Your Mind